Oct. 16, 2023

Recent gridlock in Washington over spending highlights just one of the many challenges that may persist if the federal government’s debt burden and budget deficits continue to grow at a rapid clip.

Beyond short-term political dysfunction, record levels of debt and deficit also carry significant long-term market and economic implications if not addressed.

Here’s what you need to know about the federal government’s present debt situation and its potential impact on the U.S. economy.

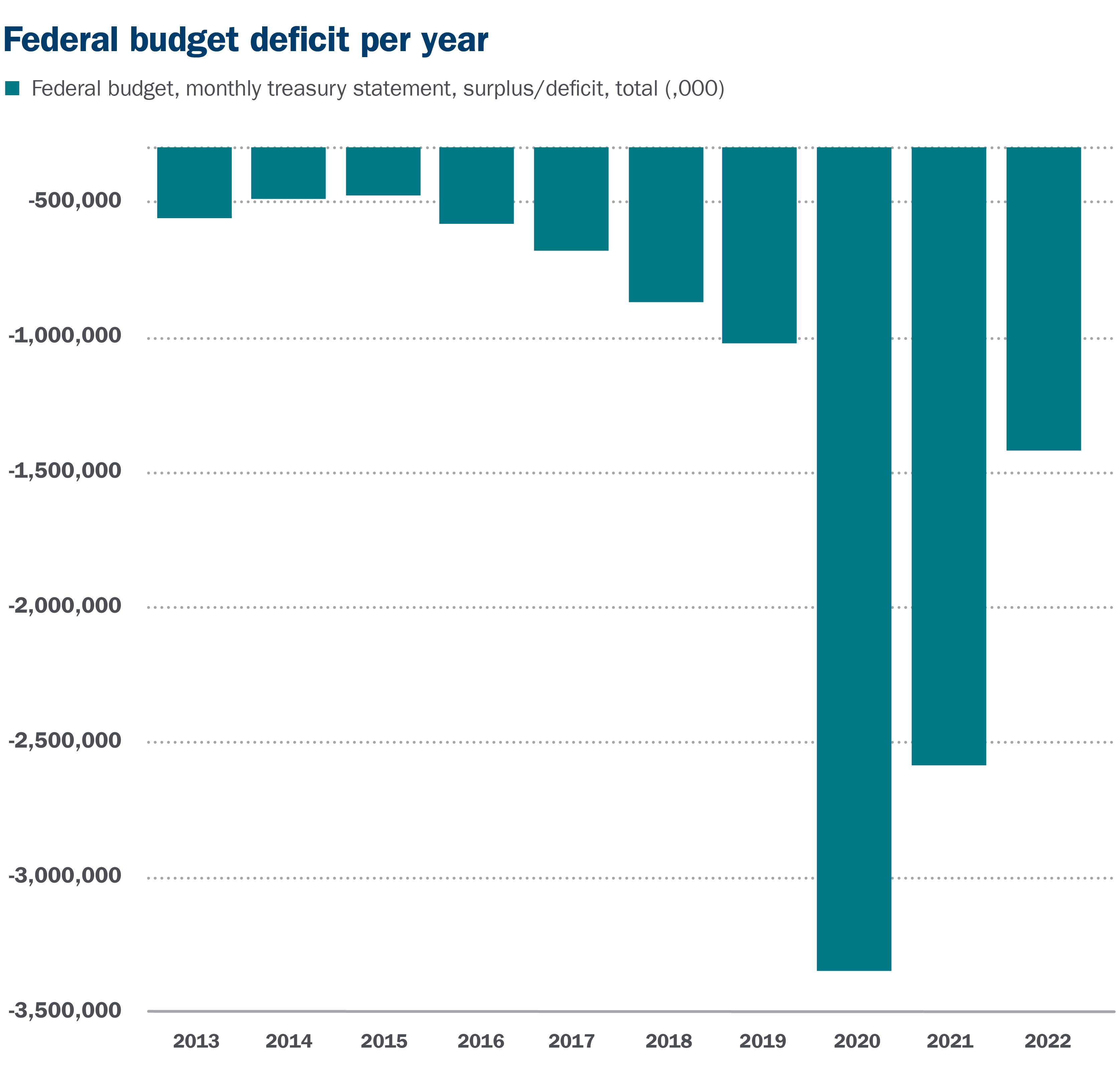

Large deficits are the new norm

Prior to the pandemic, U.S. government debt was uncomfortably high and projected to increase significantly in future years. During the pandemic, government tax revenue declined while spending rose to help support the economy.

Source: Treasury Department

This combination of lower revenues and higher spending produced record budget deficits (i.e., government spending beyond revenue in a single year), compounding the government’s debt situation.

At the end of 2019, outstanding federal government debt was $17.2 trillion, according to the Treasury Department, a figure that now stands at $26 trillion, through the end of August. For comparison, debt levels were $5 trillion before the 2008-09 Financial Crisis.

The resumption of relatively normal economic activity has not improved the deficit situation much. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) currently projects a deficit of $1.5 trillion for fiscal 2023, which ended Sept. 30. This is the smallest annual deficit the CBO expects for the next 30-year forecast period.

Source: U.S. Congressional Budget Office

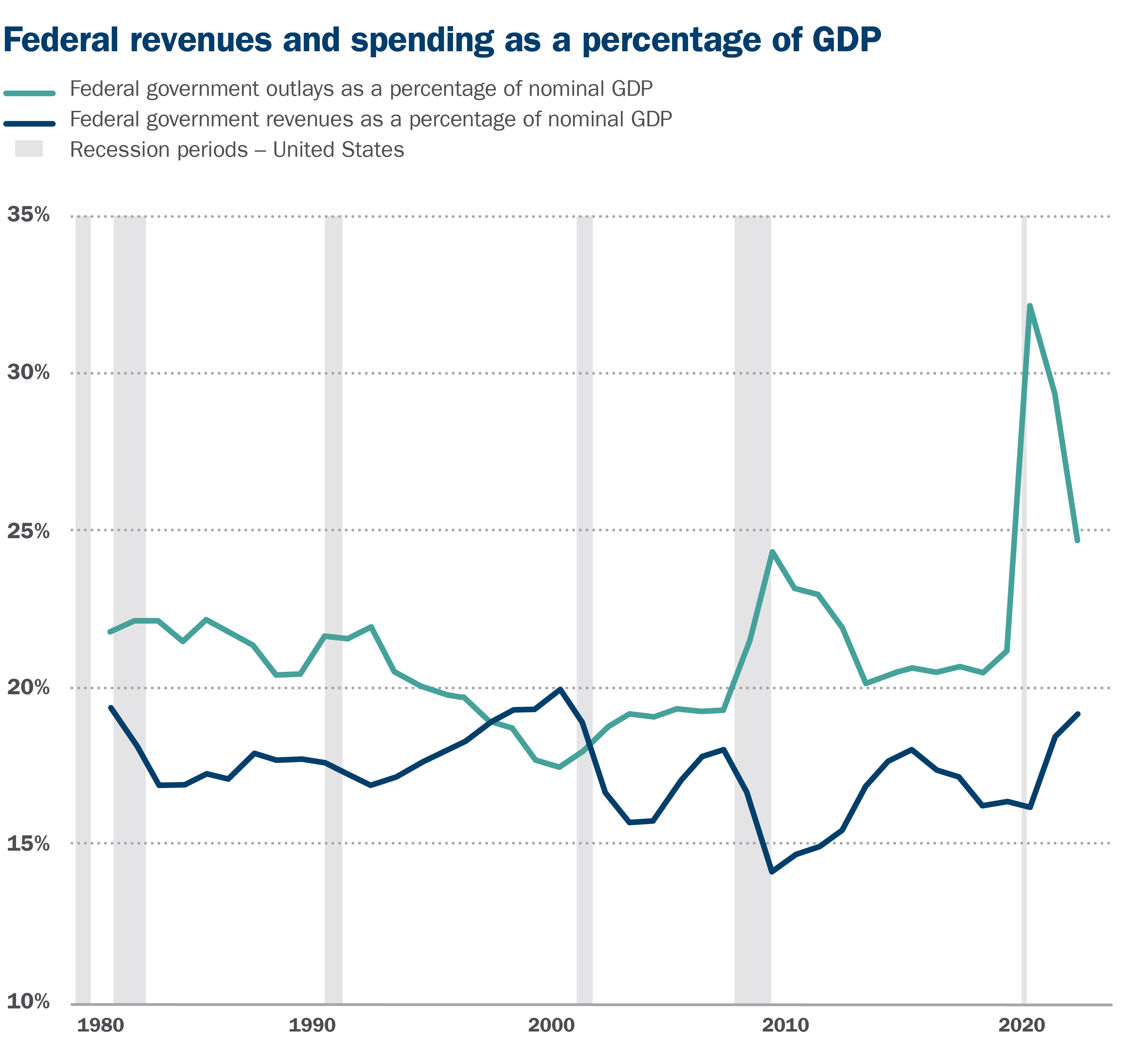

What’s driving the budget shortfalls?

The primary drivers of government debt and deficits are:

- Rising health care obligations

- Growth in the number of Social Security recipients

- Interest payments on the debt

Each driver is projected to grow faster than Gross Domestic Product (GDP) or government revenues. Social Security and Medicare obligations are essentially on “autopilot” and have accelerated in recent years as Baby Boomers retire.

Higher interest rates also present a problem. The net cost to finance new debt has been manageable due to lower interest rates over the last two decades. In a high-rate environment, however, a larger share of the government budget must be allocated to pay the interest on prior deficit spending, thus crowding out all other spending avenues. Yearly deficits must also be made up with new debt, thus creating a cycle of higher interest rates, begetting a higher debt burden, begetting higher rates … and the cycle continues.

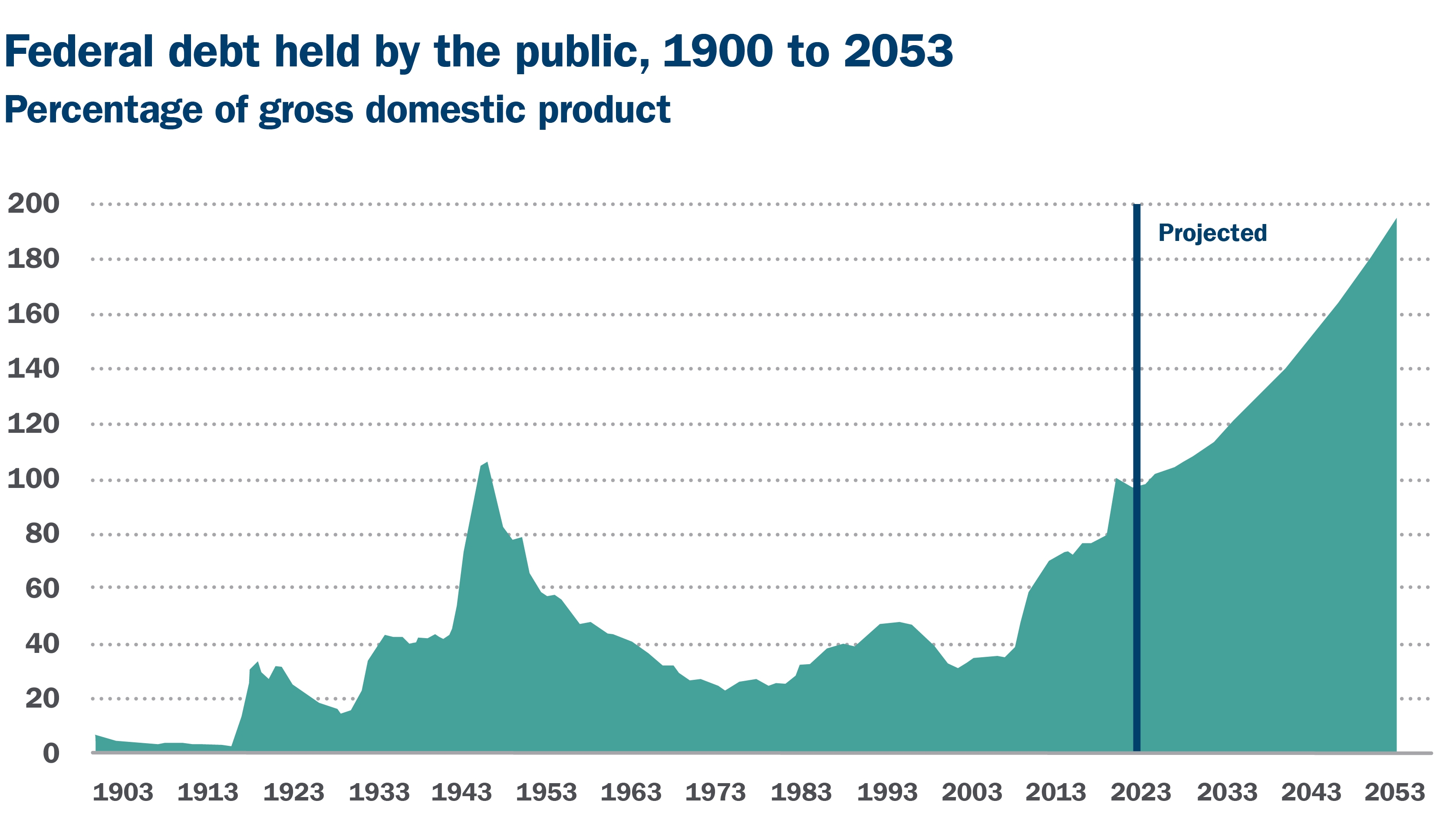

How much debt is too much?

Globally, government debt burdens are measured relative to the size of the underlying economy. Currently, U.S. government “debt-to-GDP” is 95%, the highest ratio since World War II. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projects the rate will steadily rise in the years ahead, reaching an unprecedented (for the U.S.) 181% by 2053.

Source: U.S. Congressional Budget Office

In our view, the government debt situation is not yet at a crisis point and years away from such a scenario where investors lose faith in U.S. government-issued debt. However, as government debts grow, buyers of U.S. Treasury securities may require higher interest rates in return for purchasing U.S. debt obligations that may have an increased credit risk. Please note: We still view Treasury securities as an appropriate diversifier for investment portfolios.

What can be done to resolve these challenges?

Ultimately, the budgetary challenges come down to one core issue: Government spending (based on current laws and programs) is projected to rise steadily over the next few decades as a percentage of GDP, while revenue (i.e., tax collections) generally does not.

As such, over time, elected officials must implement solutions on both sides of the budget (higher tax rates and reduced spending) to narrow deficits and, at some point, have debt-to-GDP projections “roll over” and assume a declining trajectory.

None of these solutions are socially, economically or politically easy, but neither do they have to be economically calamitous. The sooner changes are implemented, the less severe the adjustments will need to be.

Bottom line

U.S. government debt and deficit projections represent a very challenging and serious long-term economic threat, but there are solutions. The sooner elected officials set federal budget projections on a more sustainable long-term path, the less economically painful such solutions should be. Talk to your Ameriprise financial advisor if you have questions about how your portfolio may incorporate government-issued securities to help you reach your long-term financial goals.